A debate was held to weigh the pros and cons of Proposition CC on Tuesday, October 8, 2019. Kathleen Collins Becker (Speaker, Colorado House of Representatives) and Michael Fields (Executive Director, Colorado Rising Action) debated with KOAA reporter Andy Koen and Colorado Politics reporter Joey Bunch as moderators.

Proposition CC will appear on Colorado's Nov. 5 ballot.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis speaks in favor of Proposition CC, the ballot initiative to fund transportation and education by allowing the state to keep a portion of Coloradans' tax refunds, at an event on the Auraria Campus in Denver on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2019.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, seated, waits for a kickoff event in support of Proposition CC and Metropolitan State University of Denver on Oct. 2.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis addresses a kickoff event in support of Proposition CC and Metropolitan State University of Denver on Oct. 2.

Dan Ritchie, the chancellor emeritus at the University of Denver, was among the education leaders who pushed in vain, alongside Gov. Jared Polis, for the passage of Proposition CC on the November ballot last year.

University of Colorado Regent Heidi Ganahl, left, and Colorado House Speaker KC Becker debate Proposition CC for the Common Sense Policy Roundtable on Sept. 4.

Over the next few weeks, Coloradans will decide if they're willing to put more of their tax money into education and transportation.

They'll also decide how big they prefer their government, and whether they trust future elected officials to spend the windfall wisely.

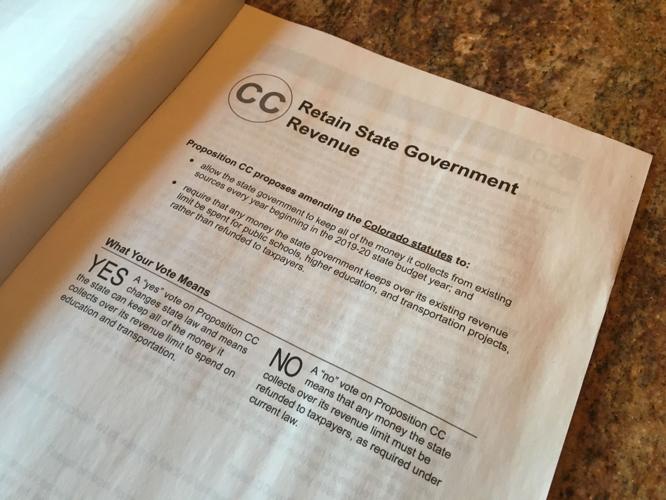

Proposition CC is one of two measures on the statewide ballot that Colorado voters are receiving in the mail this week. The election ends Nov. 5.

Prop CC aims to permanently erase rebate checks authorized by the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights, which was put in the state constitution by voters in 1992, as a way to put a cap on government spending. If the state collects more revenue than TABOR allows, which happens only in flush years, taxpayers can get an extra refund.

Next year, TABOR rebates would average out to about $38 a taxpayer, if the economy stays strong. In most years, however, taxpayers get nothing from TABOR.

Alongside Proposition CC on the Nov. 5 statewide ballot is Proposition DD, a measure that would allow sports wagering in Colorado and impose a 10% tax to help pay for state water projects.

For more on Prop DD, click here or turn to the Aug. 31 Colorado Politics print edition.

CC and DD are the only matters that all Colorado voters will see on their ballots, which started going into the mail Oct. 11.

But depending on where you live, you'll also be presented with a number of local candidates and issues.

Voters in Aurora, Lakewood and Thornton will choose their next mayor. Colorado Springs has a "de-Brucing" measure on its ballot. And Denver, Jefferson County and Douglas County are among the places voting on school board members.

In coming weeks, check back with Colorado Politics in print and online for continuing election coverage. And we'll bring you key results after the polls close Nov. 5.

- Mark Harden and Ernest Luning, Colorado Politics

But in prosperous times such as these, Proposition CC could steer hundreds of millions of dollars, split equally, into transportation, K-12 schools and higher education.

In Colorado's era of lagging schools, soaring college tuition and maddening interstate traffic jams, despite a booming economy, proponents are willing to bet voters will like that idea.

At a debate on Proposition CC Oct. 8 in Colorado Springs, which this reporter co-moderated, state House Speaker KC Becker said the constraints of that TABOR budget cap has left Colorado unable to do little more than barely keep up with the pressure of its growth. TABOR keeps the state from investing in quality schools and adequate transportation, she argued.

Michael Fields, the executive director of the Colorado Rising Action conservative advocacy group, argued back that the state budget keeps growing, but the state has spent its money on other priorities besides education and transportation, with no guarantees that future legislature won't spend the TABOR money there, as well.

When TABOR rebates are handed out, the first rebates are issued through the Senior Homestead and Disabled Veteran Property Tax Exemption, a tax break for those groups. Once that pot is filled, some sales taxes are refunded. Then, if there's anything left, the state income tax rate is lowered temporarily from 4.63% to 4.5%.

Defenders of TABOR call it good public policy that keeps the state from falling so far in debt on the whims of politicians that it can't manage during lean times. But Proposition CC backers say it keeps Colorado in a state of animated suspension unable to meet the needs of the state's growth in population and business.

“It’s not good policy to say the state is constitutionally prohibited from benefiting from a growing economy,” argues Becker, a Democrat from Boulder who carried House Bill 1257 to put Proposition CC on the ballot.

A poll of 500 Colorado voters in August by Magellan Strategies, a Republican-aligned firm, found that 54% support Proposition CC and 30% oppose the measure.

Yet Colorado voters, over the last decade, have repeatedly rejected tax increases to fund schools and roads at a higher and reliable level than Proposition CC would deliver, including two ballot measures on transportation last year.

The pitch might come down to money -- who has the most to get out the word for or against.

As of Sept. 25, Proposition CC supporters reported $1.85 million in contributions, eclipsing the total of three opposition groups -- Citizens Against CC, No on CC and Americans for Prosperity Colorado Issue Committee -- with $512,693. Of that no-on-CC total, $422,576 came from the conservative advocacy organization Americans for Prosperity, according to campaign finance records.

“Proposition CC comes with zero guarantees and weakens our Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights – the one safeguard Colorado taxpayers have against politicians eager to use our money for their own pet projects," said AFP-CO Issue Committee state director Jesse Mallory, the former Colorado state Senate chief of staff who leads the state chapter of Americans for Prosperity. "Politicians have a long history of breaking their promises in Colorado when it comes to spending hard-earned tax dollars.”

A windfall, not a stream

TABOR sets a benchmark on how much government can grow and accords an annual spending cap -- about $15 billion this year -- based on a formula that factors together inflation and population growth. The cap applies to only about one-third of the money the state spends, since the rest comes back to the state from the federal government or from user fees and other exempt sources.

That only happens in prosperous years, however. Since 1992, Coloradans have only seen refunds in nine of 26 years, including five years during the economic boom of the 1990s. Five years were exempted from TABOR to bail out a wobbly state budget, fast-track transportation projects and other needs after voters passed Referendum C in 2005.

But with the hot economy the last few years, lawmakers see an opportunity to invest in education and transportation at a significant clip.

The numbers are all over the place as the economy fluctuates. In its September revenue forecast, the state budget office lowered its previous estimate on a still robust TABOR surplus for the next two years by 38%, from $652 million to $407 million.

Besides general economic health, among the reasons the state is flush with tax revenue are the tax cuts passed by Republicans in Washington, D.C., which meanwhile erased some state deductions, as well as new taxes on online sales and the proceeds from a $1,000 monthly cap on what retailers can keep for collecting and submitting sales taxes. House Bill 1245, which passed in this year's Colorado legislative session, could deliver to the state an extra $49.4 million annually for affordable housing by 2021.

If Proposition CC passes, taxpayers would lose an average rebate of about $38 next year, which most people probably aren’t even aware they’re entitled to.

“It’s not a lot of money to lead to better schools and better roads,” Becker said in a Sept. 4 debate before the Common Sense Policy Roundtable, a nonpartisan business group, in Greenwood Village.

But that depends on if the state economy continues to churn. And with signs of Colorado slowdown, reflected in the lowered tax revenue expectations last month, and a slowing economy nationwide, that’s a mighty big if.

State spending grows

Proponents of the ballot measure, however, say the hundreds of millions of dollars could, instead, do a lot of good to subsidize low teacher pay and aging classrooms, as well as improve at least a few roads and bridges.

“These are some of the most unfunded public services in Colorado,” said Janine Davidson, president of Metropolitan State University of Denver, a proponent of Proposition CC.

Heidi Ganahl, the University of Colorado regent at-large and a prominent Republican opponent of the ballot measure, said the state doesn’t have a revenue problem. Its problem is politicians who favor spending over prioritizing.

For sure, Colorado has seen remarkable population growth -- 14.3% since 2010, a gain of more than 700,000 people. If newcomers alone formed a city, it would be the largest in the state.

Denver and Douglas counties have gained nearly 20% each, and Weld has grown by 24%.

And with great growth comes great wealth, which lawmakers in the Capitol, and in county courthouses and town halls across the state have spent in the race to keep up -- more roads, more schools, more public services.

Yet, if TABOR was meant to keep a lid on government spending, it sure wasn't screwed on too tightly.

Colorado’s spending growth rate since the end of the Great Recession -- 28% -- is the second-highest among the 50 states, trailing only North Dakota, according to a study by the Pew Charitable Trusts released in June. The national average is 4.3%.

Adjusted for inflation, 29 states, however, including Colorado's four immediate neighbors, are spending less in taxes than they were a decade ago, the study found.

While North Dakota -- flush with energy revenue -- is first for increasing its spending for K-12 education the last decade, Colorado is 18th, just ahead of Tennessee, and in increased infrastructure investments, Colorado is fourth.

The Common Sense Policy Roundtable released a study of TABOR last week that also speaks to growth in population, revenue and spending.

Adjusting for inflation, Colorado's budget has grown 69% since TABOR became law, while real household income in the state has grown by only 11.5%, CSPR found.

And though the roundtable hasn't taken an official position on CC, the researchers noted that legislators the past two years has been on a spending spree that could have directed money to the sources CC aims to help.

Last year lawmakers found $225 million a year to shore up the retirement plans for state employees, and this year came up with $175 million to pay for full-day kindergarten, which is expected to take $200 million a year to continue.

"Regardless of whether these items were sound policy decisions, they represent two new long-term obligations of state government spending," roundtable researchers wrote in their report. "The combined annual total of $425 million would equal $950 million over the next budget years. This is almost twice as much the current projections for the TABOR excess during that time period. Given that money could have been spent on other budgetary items such as increasing per-pupil funding or allocating to higher education, this highlights how annual diversions from existing state priorities accumulate over time."

In 19 pages of numbers, the think tank suggests Colorado might be wise to save the TABOR proposals as a temporary ace in the hole, rather than a regular face card at the budget table.

"Given the uncertainty of the annual growth of revenue, restrained state spending may be more useful to mitigate severe cuts during recessions, rather than funding new state programs," the report states.

Dividing school dollars

Lisa Weil, the executive director of Great Education Colorado, a statewide nonpartisan education advocacy group, called Proposition CC a “critical step” toward a more equitable state.

“Although our economy is one of the hottest in the world, we’ve got teachers working their hearts out in their classrooms who are taking an average of $600 out of their own pockets to get their classrooms ready and then they go to their second and sometimes even their third job,” she said.

The Prop CC money could provide teacher bonuses some years, extend learning options to remote parts of the state, or upgrade schools’ air-conditioning, one-time projects such as those, Weil said.

Weil said Colorado has the least competitive teacher salaries in the nation.

“Our failure to fund schools adequately is why we have a teacher shortage, class sizes are too large, and why so many districts are on four-day weeks,” she contended.

She added, “Because of an outdated formula in our Constitution, we’re preparing our students to compete in tomorrow’s job market with yesterday’s tools.

While the pile of money is apparent, some of the details on how it would be spent are now, which gives skeptics and critics pause.

The windfall wouldn’t go through regular funding channels, but would instead go to local specific needs.

But based on a per-pupil funding share, the larger urban schools -- which already tend to enjoy greater support from local taxes -- would see a much larger share than small, rural districts, where teacher shortages are tied to low pay.

Lawmakers could address that in the future, just as they decide how the money for colleges and universities is handed out.

That could give some institutions of higher learning a leg up, based on the prominence of their alumni and lobbyists at the Capitol.

Though the rising tide of revenue would be sure to lift at least most boats, the current captains will benefit the most.

“I’m tired of all the lies about Prop CC piling on the deceptive ballot language,” Gahahl said.

She said taking away a tax break is, in effect, a tax hike, even though the ballot question begins, “Without raising taxes …”

“[There are] no guarantees about how it will be spent, and it lasts forever,” Ganahl said. “The state’s budget has grown 71% in the last decade, while population has grown 15%.

"We have a spending problem not a revenue problem.”

Debatable positions

Scott Wasserman, a former top adviser to then-Gov. John Hickenlooper who leads the left-leaning Bell Policy Center, gets frustrated with political rhetoric that tangles up progress on education and transportation, which nearly everyone agrees need the state’s dollars and assistance.

“They win when we argue about things that aren’t real,” he said. “CC does not change your tax rate. It does not raise your taxes. But they want to have an argument about whether or not it does. But political rhetoric isn’t the same thing as economic analysis or real tax policy.”

In July, the Bell Policy Center released a detailed analysis of the proposition.

Most notably, there is nothing new about what it proposes: de-Brucing, a term that refers to Douglas Bruce, the El Paso County anti-tax advocate and convicted tax felon who authored and led the campaign to pass TABOR.

Fifty-one of Colorado’s 64 counties -- plus 230 out of the state’s 274 municipalities and 174 pf the state’s 181 school districts -- have de-Bruced at one point or another to steer money into local transportation, education and other needs.

“When times are good is exactly when the state should be investing in things, because times will inevitably be bad, and we will regret not having made good use of good times to invest in things like roads and schools and all the things we talk about,” Wasserman said.

He said there’s a disconnect for most people of why Colorado has such a robust economy, yet its schools and roads are in dire want. The reason, in his estimation, is constitutional clamps on the state budget put in place via measures such as TABOR.

“That’s the reason we don’t invest enough in those things,” he said.

George Brauchler, the politically engaged district attorney and former Republican attorney general nominee, is leading the campaign against passage, and characterizes the question as one of trust in politicians.

"Because it's a statutory change, any legislature -- this one or future ones could simply get among themselves and say, 'Let's vote to send all the money that fits under CC somewhere else,' and we'd be powerless to do anything about it," he said.

Transportation mistrust

For certain, the money from Proposition CC won’t fix a decade of inequity for schools and roads.

If the rosiest projections come true and the state gets back $4 billion, and even if the entire windfall went into transportation, it would still be less than half the backlog of $9 billion in road and bridge needs left by the Hickenlooper administration.

Gov. Jared Polis hasn’t yet rolled out his transportation plan, but he’s signaled clearly that he favors mass transit -- including Front Range commuter rail -- over pouring more money into asphalt, which further clouds how the transportation dollars might be invested.

Tony Milo, executive director of the Colorado Contractors Association, the builders of most public projects, is backing CC because progress is better than being stuck, which is where the state’s transportation planning has been for years.

“We think something is better than nothing,” he said at the Proposition CC kickoff in Denver.

But he acknowledged there were no guarantees on when or if that money would be available, or how it would be spent.

“It’s going to be volatile and it’s going to be unpredictable, but in the good years there’s going to be some money there and we’d like to be a part of that, because we know we need it,” Milo said.

Two measures that would have funneled tax dollars to transportation -- a tax hike and a requirement to use existing budget, respectively -- failed at the ballot box just a year ago.

But the fix has to come from somewhere, Milo said.

“Eventually, I think we’re going to have to go back to the voters for a dedicated funding source,” he said. “We just have to figure out what that funding source is.”

TABOR test

TABOR is sacred doctrine to conservatives in Colorado, and the cap on government that has survived the test of time, so far.

The same August Magellan Strategies poll that found 54% support for Proposition CC also reported that among 59% of voters familiar with TABOR, only 36% would support its full repeal. And 62% of all those surveyed like TABOR's other major aspect -- its requirement that any proposed tax hikes must be submitted to voters.

Still, whether Proposition CC passes or fails, there already are discussions and lawsuits in place to take TABOR down completely. CC is a test of the strength of that movement and a measure of public attitudes toward that end, both sides agree.

In a separate interview before his Oct. 8 debate with Becker in Colorado Springs, Fields, the Colorado Rising Action executive director and Prop CC foe, predicted the effort wouldn’t stop there.

“I think CC is definitely part of broader push to repeal TABOR and eventually enact a progressive income tax,” he said. “If proponents can’t win a de-Brucing ballot issue with this biased ballot language, they have no real path forward to repeal TABOR or raise income taxes.

“If they do win, you will see more resources and focus on getting rid of the rest of TABOR.”

Polis -- who appeared at the Oct. 2 yes-on-CC campaign kickoff event -- pointed out that de-Brucing isn’t a new idea even in 16 of what he considers the most conservative counties across Colorado.

“There’s a very strong coalition of Republicans, Democrats and independents that are are saying we shouldn’t have an arbitrary, outdated formula in our constitution for distributing these funds,” Polis said. “We should simply trust the voters.”

Polis said Prop CC has accountability built into it, with annual audits.

“This is something that can really bring people together, just as it has in counties that are 70% Republican and 70% Democrat in their votes, they’ve all united behind this principle of being able to use the funds they collect, rather than have an arbitrary, antiquated formula in the Constitution that forces them to do things against the people’s will," the governor said.

State Sen. Kevin Priola, a Republican from Henderson, co-sponsored the bill that put Proposition CC on the ballot.

One of the first elections he voted in was to put TABOR in the state constitution in 1992. Four years later, the fifth-generation native of Adams County (and now a father of two) graduated from the University of Colorado.

He’s never wavered from his belief in conservative principles, he said.

He said that one of the reasons TABOR passed in the early 1990s was because it carried a “direct democracy” component of letting Coloradans decide whether to be taxed.

“When you’re exercising a part of TABOR you can’t be undermining TABOR,” he told Colorado Politics. “TABOR explicitly allows for this.”

If Proposition CC passes, voters would permanently lose their TABOR tax refunds, but they would retain the right to vote on future tax hikes and most major loans, he noted.

Priola called it a fiscally rational and responsible step to invest now rather than struggle later.

“I’ve spent $500 to $600 on two new tires the last three to four years hitting potholes,” he said.

Giving up a few dollars on his tax returns during prosperous times sounds like a pretty good deal to Priola.

Rural doubts

Last year, Club 20, the organization of government, businesses and other groups that advocates for the Western Slope, was one of the founding members of the coalition to pass Proposition 110, the failed ballot question to pass a statewide sales tax to address the Colorado’s backlog of transportation needs.

This year, Club 20 is sitting out the TABOR fight.

The club’s board of directors heard presentations, both pro and con, on both November ballot measures during their fall meeting in Grand Junction last month.

“One of the concerns we had [with Proposition CC] is that this is in perpetuity as opposed to being sunsetted,” Club 20 President Cindy Dozier told Colorado Politics.

She added that the feeling in the room was that “if we wanted to support transportation, this was not the mechanism for it. We also have no guarantee that those dollars would come to the West Slope and that the dollars raised through CC would not move the needle much.”

Some board members were concerned about how the ballot question would affect the integrity of TABOR, Dozier said.

“There’s a lot we liked about it but some we didn’t, so we decided not to take a position,” said Club 20 board member Harry Peroulis of Mesa County.

“Loving all of it is what we need, especially with the word perpetuity in it and no sunset,” Peroulis explained. “Conservative people don’t like that open-ended” question.

“No one has a crystal ball on what will happen down the road.”